Jack the Ripper

He Stalks the Medical Corridors and Courtrooms --

and Scares the Hell Out of Washington's Doctors

By Kim Eisler

This article was originally published in October, 1991 in Washingtonian Magazine.

Hands that have skillfully executed open-heart surgery quiver. Obstetricians who have dealt with the darkest fears of couples are rendered speechless.

All you've done is mention Jack H. Olender. Slipping that name into a conversation with a physician is akin to joking to airport security that you have a bomb in your suitcase.

Jack Olender is the lawyer who sues doctors. And not just any lawyer who sues doctors. The Washington yellow pages contain some 30 pages of advertisements for lawyers who make their livings off the occasional misdiagnosis or slip of the knife. Many are ambulance chasers; most are flicked away by insurance company attorneys.

Jack Olender is the lawyer who sues doctors. And not just any lawyer who sues doctors. The Washington yellow pages contain some 30 pages of advertisements for lawyers who make their livings off the occasional misdiagnosis or slip of the knife. Many are ambulance chasers; most are flicked away by insurance company attorneys.

Not Jack Olender. Single-handedly -- he has no partners -- he has hit the million-dollar jackpot for his clients 26 times, making him one of the nation's most successful personal-injury lawyers.

But the money is the least of it. In a city where antagonists usually are civil, one prominent physician mentions that it might have been worth a large malpractice judgment to have clipped off a certain appendage when Olender recently underwent a urological procedure. "It would have been worth a million or so," the doctor muses. "We would have all chipped in."

Another doctor, responding to a letter soliciting comments about malpractice, wrote of Olender: "He is a very powerful, arrogant, abusive, and vindictive lawyer ... My insurance does not allow me to talk to you for fear of reprisal ... I have not been sued by Mr. Olender, but I despise his tactics. He has absolute control of the city ... He goes beyond the function of a malpractice attorney and actually enjoys humiliating obstetricians and dictating to them how to practice. In the meantime, he is making millions ..."

More than a dozen obstetricians interviewed about Olender blamed him for everything from too many Caesarian sections to running obstetricians out of the District.

Most lawsuits against doctors are settled quietly, with a relatively small sum changing hands, according to Stuart Gerson, head of the Justice Department's civil section. According to a Harvard University study, fewer than 2 percent of the people injured by doctors actually sue.

But statistics hold little meaning for the Ob/Gyn in Washington who writes an annual malpractice insurance check for $90,000 or more. And especially for one who wakes up to find a process server on his doorstep.

For the doctor, a lawsuit is traumatic. For the victim of a medical mistake, it is often the only hope of recovering the costs of future medical care. For the rest of us, the threat of suits and the sometimes seemingly outrageous jury verdicts affect the cost of health care, as well as the availability of doctors who practice in such high-risk fields as neurology and obstetrics.

Most lawyers who take these cases get nothing if they lose. But when they win, they can become millionaires overnight. That's what happened to Olender.

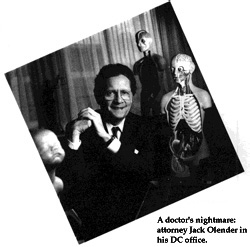

Jack Olender is well over six feet tall; his thick shock of hair, pushed back from his forehead, is black for his 56 years; his skin is pale. He abhors small talk, never tires of talking about injury. In his office, he is surrounded by cutaway medical models of the human body.

Olender seems to enjoy intimidating his potential victims. He recently attended a physicians' conference at Georgetown University Hospital, sitting in the front row. After a break, he found an obscene note on his chair.

"I was not there to make a statement," Olender says. "I was there strictly for education. The more I know, the more effective I can be."

A doctor who helped organize the conference couches it differently. "Olender used our conference to learn things that he can use against us. How cocky can you get?"

To which Olender replies, "Correct. I've attended a number of such conferences."

In mid-June, Olender was a panelist at a conference held at the Capital Hilton Hotel to discuss the political issues surrounding medical malpractice. The Bush administration has proposed legislation to cap the amount of money victims of malpractice can receive for pain and suffering. Olender was seated near one end of the cloth covered table, right next to Dr. Daniel Ein, president of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia. "I guess I'd rather be at the same table than at opposite tables," Ein quipped.

When it was Olender's turn to speak, he didn't pull any punches. The reason doctors want changes in the civil code, he said, is that "they want to make it less onerous to commit malpractice. They want to make it cheaper to kill and maim."

Stuart Gerson, the Justice Department lawyer who has drafted the administration's malpractice-reform proposals, glanced up. "You have a delicate gift of understatement," he said.

Before the conference was over, Olender escalated his attack on the medical profession, claiming that more than 89,000 people a year are "murdered" by doctors, almost twice the number of people killed in car accidents. Another 354,000, he claimed, were injured in hospitals. "If that's not an epidemic, I don't what it is," he said. Asked about the figures later, Olender said they were "extrapolated" from a study about malpractice in New York City.

Listening to the doctors, then to Olender, does not instill much confidence that the debate over medical malpractice -- how to avoid it, how to protect the integrity of the medical system, and how to ensure victims' legitimate rights -- will be easily settled.

In many jurisdictions today, including the District of Columbia, there is no limit to the amount of money that an injured person can collect for intangible "pain and suffering." (Virginia and Maryland do limit such awards.) Compensation for actual damages can be estimated: The costs of taking care of a brain-damaged baby or someone rendered quadriplegic by an accident may vary, but an insurance company can at least estimate the worst-case expenses. But when it comes to paying for a victim's pain and suffering, a jury can award any amount.

"It's totally unpredictable," says Gerson. "The insurance company has no idea what the judge and jury are going to do, so they have no choice but to set their rates at the highest end of the scale."

Gerson's proposal would cap noneconomic damages at $250,000 per person -- an arbitrary figure, he admits. "Zero would be better," he says. "Our figure is based on political reality."

The bill also would restructure malpractice settlements so that money to compensate for actual damages would be paid out over time rather than in one lump sum. Gerson cites the hypothetical example of an injured child who is awarded $5 million to cover the cost of a lifetime of medical care, then dies of his injuries the next day. "This money is not intended to compensate the parents," Gerson says. "This money has been paid out for something very specific, and it shouldn't become a windfall."

For the public, the issues include the cost and availability of good medical care. Most areas of Washington, for example, are served by an adequate supply of good Ob/Gyns; they can charge their insured and well-to-do patients enough that, even after paying insurance premiums of up to $100,000 per year, they will still take home $250,000 to $300,000, according to many of the doctors interviewed for this story.

But in other parts of the city and the nation, Gerson says, patients cannot afford to pay doctors enough to cover high insurance costs. So doctors have abandoned poorer areas, leaving parts of DC, for example, with Third World-like rates of infant mortality and low birth-weight.

Gerson says the problem lies in a system that allows open-ended, excessive recoveries. Physicians say the problem is lawyers like Jack Olender.

Doctors who have never met him in court accuse Olender of relying on emotional arguments and slick courtroom tactics, but not one of the half dozen or so who repeated such charges was able to cite any specific examples.

Lawyers who have opposed Olender say his technical legal work is impressive. "I have no knowledge of him acting in any improper way," Gerson says. "A lot of what he says and does tends to be of a rhetorical nature ... He does a good job for his client.²

At the center of the controversy between Olender and the doctors is the argument over "defensive medicine." To Olender, defensive medicine means taking every possible precaution -- having doctors practice as if they are going down a checklist.

Doctors say that practicing that way would be too expensive, too time-consuming, and usually unproductive. "l see a huge number of patients, " says one physician, "and I can't tell you how many unnecessary tests we order up across the board."

Olender responds that a small percentage of such "unnecessary" tests turns up useful information.

His response to calls for such reforms as damage caps and compulsory structuring of settlements -- to anything that lessens the potential liability of doctors -- is predictable: "These proposals abet, encourage, and promote more malpractice against patients," he says.

For the doctors, any relief will be welcome. For them, a lawsuit is about much more than money. The rigors of litigation, the damage to a reputation, the hours wasted in depositions and hearings -- even if the case never goes to trial -- all take a toll.

And anyway, when doctors do make mistakes, they do not mean to do injury. A doctor can try to save someone's life and get pilloried for failing.

Doctors grapple with the question of how to punish peers when they know that they themselves could so easily make the same mistakes through fatigue or simple error. It's all complicated and difficult and uncertain.

But not to Jack Olender. "Let the doctors stop committing malpractice," he says. "Then they won't have to worry."

Jack Olender was born on September 8, 1935, in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, ten miles southeast of Pittsburgh. His father was a Jewish immigrant from Eastern Europe who ran a produce store.

Both of Olender's older brothers died in childhood, one as a result of a sledding accident, the other of influenza. Because of these tragedies, Olender was reared in a protective environment. He says he had to quit his high school debate team because his father wouldn't let him ride in a car at night to competitions.

Through college and law school, Olender lived at home, commuting to the nearby University of Pittsburgh. In 1959, he was named articles editor of the law review. He wrote an eighteen-page law school treatise, "Donation of Dead Bodies and Parts Thereof for Medical Use."

Olender finally left home at the age of 24, when he came to Washington and enrolled in a George Washington University law program in forensic medicine. He had realized that a knowledge of forensics could come in handy after he served a summer clerkship with a Pennsylvania lawyer who handled personal injury cases, he says.

Olender paid for the course by working as a teaching assistant. Then he hung out his shingle on his own -- "not something I would recommend to anyone," he says. ''I was not immediately a smashing success."

For sixteen years, Olender says, he was just another solo practitioner trying to eke out a living on auto accident cases and whiplash injuries. He lived with his wife, Lovell, in a modest apartment near the GW campus.

In the late 1960s, Olender was trying a whiplash case in Montgomery County Court in Rockville. His client was offered a settlement of $2,500. Olender refused to take it and charged into trial. The jury came back with an award of $2,500. "You couldn't exactly say it was a big win," Olender admits.

But in the courtroom was the grandfather of a more seriously injured accident victim, and he liked Olender's moxie. Olender took the case and won his biggest judgment ever, $10,000.

The lawyer's fortunes really changed in 1976, when he persuaded a jury to award $2.6 million in damages to a child born with cerebral palsy -- a condition caused, Olender argued, by a deprivation of oxygen that resulted when the breech baby's feet were pulled out of the womb.

Olender's case could be helped by the testimony of a nurse who had been in attendance, but Olender couldn't find her. Then, as he had in Rockville, Olender got lucky. He was in New York interviewing a potential expert witness when he mentioned the nurse's name. The doctor knew her -- she had moved to New York. Her testimony won Olender his case.

Having made real money for the first time in his life -- a standard one-third contingency fee would have given him around $800,000 -- he bought a Cadillac Fleetwood and moved to a 3,500 square-foot apartment in the Watergate.

In law, nothing begets success like success. It wasn't long before Olender had his pick of cerebral-palsy damaged baby cases. Not that they just walked in the door. Once he had money, Olender started getting his name out in public. He advertised in teacher-of-the-year awards-banquet programs, anyplace he could get the attention of young mothers. He began advertising in the back of the Washington Post Magazine: "BRAIN DAMAGED BABIES AND CHILDREN.²

Olender spread his money around town -- making political contributions, hosting parties, giving awards. The walls of his office are covered with framed clippings of his adventures and photos of his check presentations. Recipients of the Olender Peacemaker Award range from then-Redskins quarterback Doug Williams to Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. Olender's annual Christmas party at the J.W. Marriott Hotel is one of the season's biggest, complete with a marching band.

The once-shy kid from McKeesport now runs with celebrities like broadcaster Larry King and lunches regularly at Duke Zeibert's, where he walks to his table talking on his portable telephone.

Olender's most frequent opponent in court is Joseph Montedonico, who has defended many Washington doctors over the past twenty years. He describes Olender as a zealot.

"He believes he has a cause,'' Montedonico says." He doesn't have any kids to put through college. He's not looking for a quick fee at this time of his life. There's no negotiating with the guy."

Montedonico says he recently offered an Olender client a $1-million settlement on an amputated leg. Olender rejected the offer out of hand and then told the client that if he wanted the settlement, he would have to find another lawyer to accept it. The client stuck with Olender.

Olender's account varies only slightly: "I think what I said was that I couldn't be a party to an offer so outrageous." Besides his stubbornness in negotiation, Olender differs from many attorneys in that he refuses to seal settlements from the press. One interpretation is that he wants the publicity to keep business coming in. Recalling his sixteen years of financial struggle, Olender confesses that he, like many lawyers, has an abiding fear that the day will come when no new clients walk through the door.

But that is not the whole answer. Doctors say Olender won't seal settlements because he wants to humiliate them. He says, "I don't want what the doctor did hidden under a secrecy agreement."

Even Olender's legal colleagues are sometimes critical of his tactics. Several told me that they don't like the attention Olender's public verdicts focus on the amount of money clients receive -- and on the contingency fees attorneys make.

"I think a lot of us wish he were a little quieter," says one. "A lot of what he does causes people to contemplate changes in the law that could hurt all of us." Adds a prominent competitor who regularly seals settlements: "There's a much more humane way of going about this business."

But for Olender, the practice of personal-injury law is only part business. It is also a mission. Olender attributes his zeal to the experience of seeing injured people crying out for help.

When Olender sits in front of a crowded conference and calls doctors "killers and maimers," he seems to believe it. He is slightly more restrained in private. "There are a small number of physicians who commit more than their share of malpractice," he says, "and that's where my anger is directed."

His most publicized and controversial case, however, involved three highly respected obstetricians, against whom he won a $10-million judgment three years ago.

Olender claimed that a woman 32 weeks pregnant went into the hospital in labor, then waited five hours before undergoing a Caesarian section, a delay that he said caused permanent brain damage to the baby. The doctors believe that the damage already had been done.

Convinced that his clients had done nothing wrong, the doctors' attorney rejected Olender's offer to settle for $4 million. A jury awarded the child's family $10 million, $6 million more than the physicians' insurance coverage.

To avoid appeals, Olender agreed to take the $4 million he had offered to accept in the first place. Out of that, he collected $1.7 million, according to documents filed in US District Court.

Asked about the size of the fee, Olender replies, "It was a large amount of work."

On the telephone is an obstetrician-gynecologist. Like most of those I have talked to, he refuses to be named in a story about Olender.

"I've never been sued," the doctor says. "But eighty percent of my colleagues have been. Jack Olender is the single most important force in a decision I have made to stop delivering babies. It's not a question of if, it's a question of when I stop. Sure, there are plenty of lawyers all doing the same things, but Olender leads the pack. The others see his success and follow the trail."

Adds one prominent doctor, "You always know he's there.''